The first baby boomers turn 80 in just five years—is the U.S. ready for their housing and support needs? Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies just analyzed the data, and the answer is … no. But forewarned is, hopefully, forearmed.

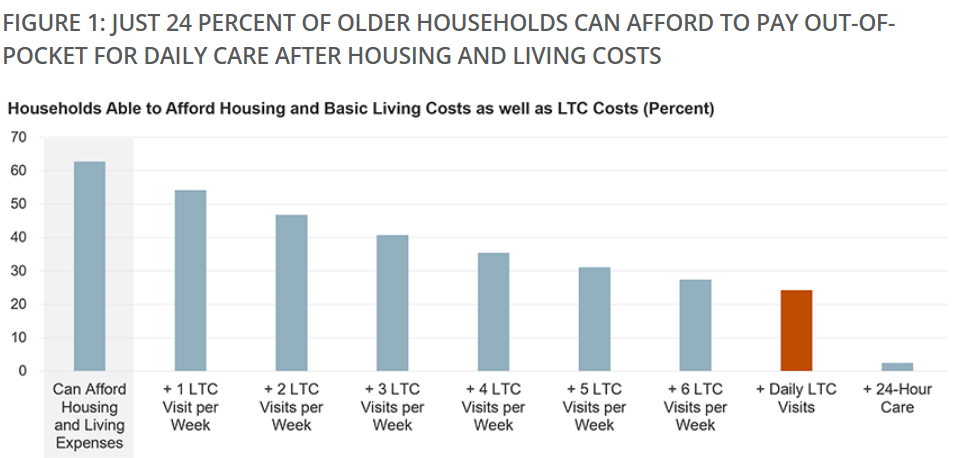

The study found that, after paying for housing and basic living expenses, only 24% of single and partner households age 75 and over had sufficient income to afford a daily paid visit from a home health aide. And the numbers were worse for renters, households of color, and those with functional difficulties more likely to need care services.

A majority of older adults will need long-term care (LTC) services at some point, including assistance with dressing, bathing, and managing medication regimens. Most older adults prefer this to be home care, but that is out of reach for many. Daily in-home visits by a health aide in 2021, at the median national rate, added up to $41,000 per year. Not only does medical insurance, including Medicare, not cover most LTC needs, but relatively few older adults have private long-term care insurance. LTC services at home are most likely to be paid for by Medicaid Home and Community Based Support (HCBS) waiver programs; these do not operate as entitlements, vary in coverage and availability by state, and are only available to those enrolled in Medicaid. In reality, most LTC services are provided by unpaid caregivers, such as family and friends, who have to shoulder this heavy burden.

Of the nearly 10 million households in the sample, only one quarter had enough income to pay for a daily care visit on top of housing and basic living costs. Partner households were better: 43% were able to cover a daily visit serving both partners, compared to 19% of those living alone. And home ownership matters: 30% of homeowners were able to afford housing, basic expenses, and daily care, compared to less than 9% of renters.

Black and Hispanic households were least likely to afford care, with only 14 and 11%, respectively, able to fund LTC services out of income alone, compared to 26% of white households. And just 19% of households with a resident who struggled with mobility, self-care, and/or independent living were able to afford a daily care visit.

A daily paid visit was out of reach for most, but slightly more than half of the households sampled could afford one visit per week; 30% could afford 5 weekly visits, which could at least provide a small respite to unpaid family caregivers. Only 63% could afford housing and basic costs of living, without even considering the cost of daily LTC visits. The rest simply lacked the money for any LTC care services.

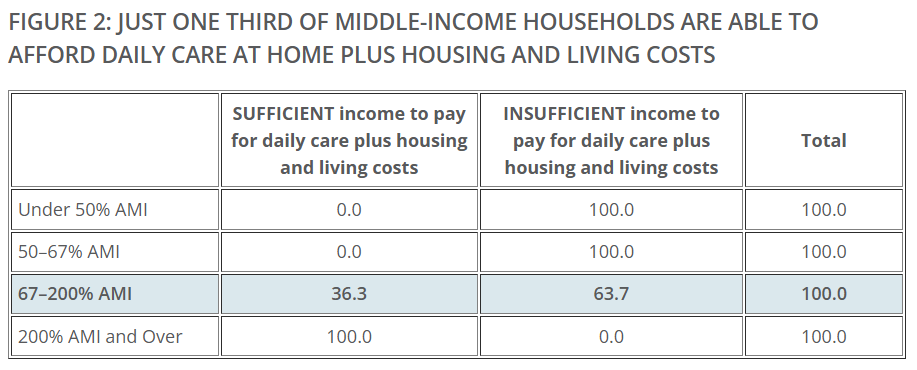

Not surprisingly, households earning under 50% of area median income (AMI) were unable to afford a daily care visit. But 64% of those earning between 67 and 200% AMI (what the Pew Research Center defines as “middle income”) couldn’t afford it, either. This group is caught in the middle: far less likely to be eligible for Medicaid-covered LTC services, but lacking sufficient income to pay out of pocket.

The good news is, many middle-income households have housing wealth that could be tapped. Those that owned their homes free-and-clear could, in theory, borrow up to 80% of their home’s value; in the sample, those funds could allow 1.6 million households to fund LTC services for five years, increasing those able to afford daily care from 24 to 41% (at 2021 prices).

The caveat is that not all owners would likely secure financing to extract this much equity. Given the disproportionate share of Black and Hispanic households unable to afford care, liquidating home equity limits potential intergenerational wealth transfers and may exacerbate the persistent gap in homeownership by race and ethnicity. Renters, of course, have zero home equity, and would see no improvement in LTC affordability.

With rising costs of already high-priced housing and care, and federal funding more volatile than ever, there’s no easy solution. Fully funding Medicaid HCBS would help those with the greatest affordability needs, while coverage of LTC services by Medicare would help millions more. Housing needs must also be addressed to help older households make ends meet, such as through expanded rental subsidies as well as home repair and modification assistance to ensure the home is a suitable and comfortable place in which to receive care.

Click here for more on the Harvard Joint Center for Housing