After the pandemic began, home prices increased at a never-before-seen rate. In earlier studies, Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) showed that throughout this time, property prices increased particularly quickly in the U.S.’ more remote regions, including rural counties. Building on this data, Alexander Hermann, JCHS’ Senior Research Associate and Peyton Whitney, Research Analyst, examined the types of rural towns that had the biggest price increases in a new working paper.

Experts found that prices in rural areas doubled the rate of appreciation in the three years before to the pandemic, rising approximately 36.1% between March 2020 and March 2023 based on data on property values in non-metro counties. However, prices increased even more quickly (46.8%) in counties with a large percentage of vacation and second homes—places that frequently have high natural amenity values and robust tourism sectors.

An influx of people into rural areas has contributed significantly to the significant increase in housing values. During the pandemic, remote work became increasingly popular, enabling employees to relocate farther from their place of employment. For the first time in at least 10 years, net domestic migration—a significant factor influencing housing demand—turned positive in non-metropolitan counties. Prior to the pandemic, there were 77,900 fewer people living in rural regions between 2017 and 2019. However, that tendency drastically changed between 2021 and 2023, with rural areas acquiring a net 540,400 residents.

As a result, rural communities across the nation saw extremely rapid increases in home prices. Additionally, rural counties in the Northeast and West saw particularly significant price increases. Typical home prices increased by 40.5% in non-metro counties in the Northeast and 40.7% on average in non-metro counties in the West in the three years after the epidemic began (Figure 1). The Midwest (31.4%) and rural South (35.5%) saw significant price increases as well. In contrast, pre-pandemic home price increase was more moderate across all regions, ranging from 13.6% in the Northeast to 20.9% in the West.

Vacation Counties See Influx of Migration Trends

In vacation counties, where over one-fifth of the housing stock is unoccupied for sporadic or seasonal usage, net domestic migration was particularly high. About 14% of the non-metropolitan counties in our sample are vacation counties, which are particularly prevalent near beach towns on the East and West Coast, in mountain villages in the Northeast and Mountain West, and around the Great Lakes in the upper Midwest.

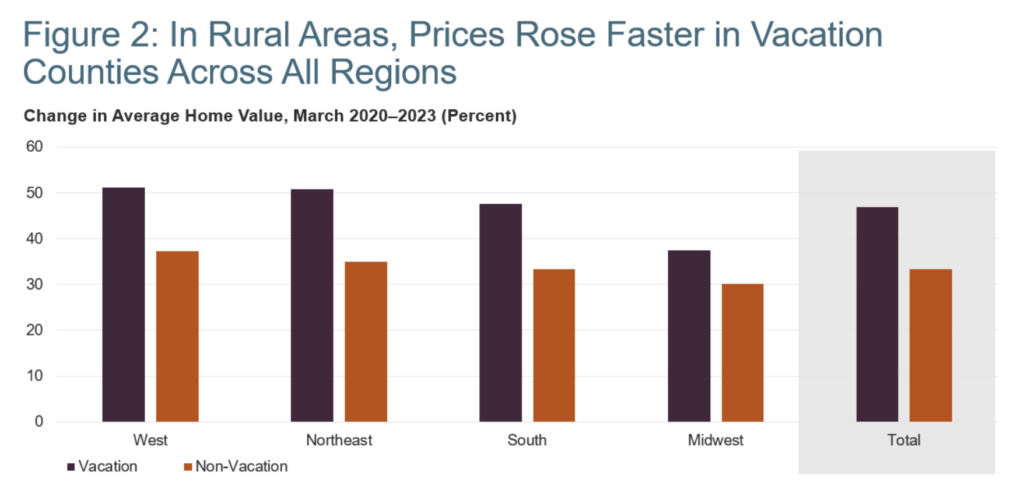

Home values in these areas increased from 17.4% in the three years prior to the pandemic to an amazing 46.8% between March 2020 and March 2023. Home prices increased more quickly across all regions in rural vacation counties (Figure 2). Home prices increased by 51.1% in Western vacation counties, an estimated 50.9% in the Northeast, some 47.5% in the South, and 37.4% in the Midwest in the three years after the outbreak.

In the research, we also discuss the types of rural communities that had the greatest price increases following the pandemic, focusing on key characteristics of urbanization and rurality. Regression models suggest that home prices increased slightly more in counties near metro areas, with lower densities, and with smaller urban populations, but also confirming the quick price gain in vacation counties.

Note: Data are for non-metro areas only. Vacation counties have more than 20% of the housing stock vacant and available for seasonal, recreational, or occasional use.

Experts examined key indices of rurality and urbanization in particular when reporting on the types of rural communities with the greatest price appreciation following the epidemic. Regression models suggest that home prices increased slightly more in counties near metro areas, with lower densities, and with smaller urban populations, but also confirming the quick price gain in vacation counties.

Vacation destinations with robust tourism sectors frequently depend on low-wage, seasonal service workers. Strong domestic migration can exacerbate the strain of growing housing costs and a shortage of available housing for these workers and many existing households. The immediate needs of these citizens could be met by additional public assistance, such as housing vouchers, property tax abatements, first-time homebuyer assistance, and other housing and non-housing assistance programs aimed at lower-income households.

Further, even as the need to build more homes grows, homebuilders face particular challenges in rural housing markets, such as high infrastructure development costs and a shortage of construction workers. The need to build both market-rate housing and more cheap housing types, such manufactured homes, at scale in rural areas will only grow if domestic migration trends continue and more people move into these areas.