Experts say the phrase is buzzing around circles these days—“social housing,” ideally, a system in which public and nonprofit entities develop, own, and manage housing for low-income Americans.

Inspired by examples in Europe, proponents of the concept envision a network of energetic, entrepreneurial, mission-driven agencies running the system.

Historian Alexander von Hoffman, in papers penned for Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, endeavors to determine whether the public housing program is in fact a critical component in a contemporary affordable housing framework.

Followers of America’s housing-policy history will find the conversation familiar.

“Almost a century ago, a small band of progressive-era reformers and socialists looked to Europe for models of affordable housing programs, which they referred to as municipal, public, or, yes, social housing,” von Hoffman explained in the essay “Problems and Progress: Public Housing in an American Social Housing System.”

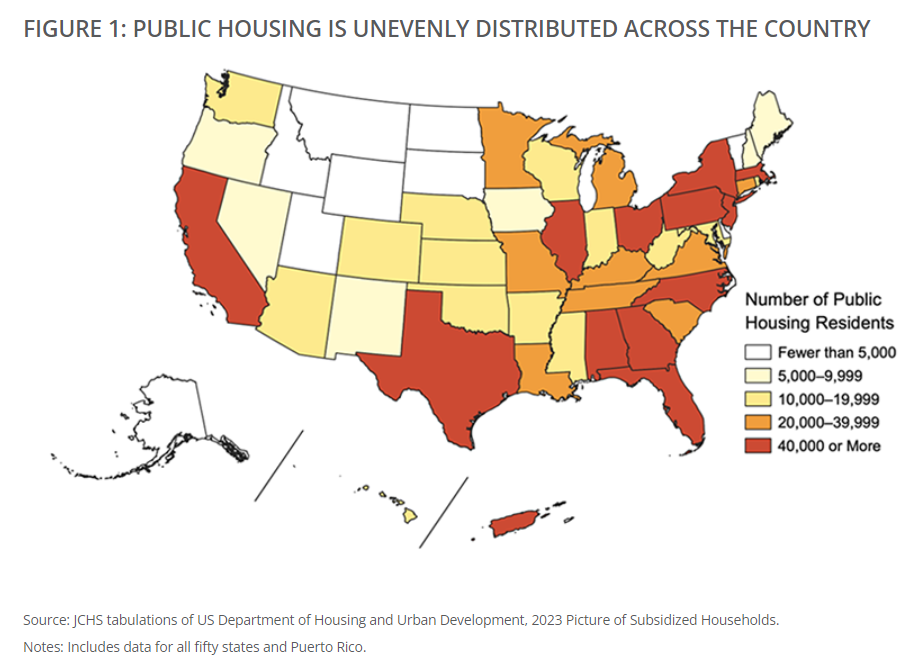

Public housing, the oldest and largest supplier of permanently affordable housing in the U.S., has often been left out of the conversation about tomorrow’s “social housing” system.

Von Hoffman notes that, since its start, public housing has been beset by challenges.

After coordinated political attacks came local opposition to affordable housing programs, campaigns which contributed to the federal government’s less-than robust support and provisions.

Routinely segregated by race, public housing increasingly became the housing of last resort for those with the lowest incomes.

Vacancies, physical deterioration, and crime plagued large projects in big cities by the 1980s, Von Hoffmann said.

With the next rounds of reform, locally established public housing authorities (PSAs, which had, until then, contributed significantly to the public-housing program budget) were allowed to sidestep traditional public housing procedures.

Reforms encouraged PHAs to move previously discrete public housing funds to pay for a range of operations, to develop mixed-income residences with private partners, and to convert public housing contracts to project-based Section 8 subsidies, von Hoffman explained.

“With these measures PHAs could redevelop their properties with their own subsidiary companies or private partners and build mixed-income communities by combining public housing allocations with low-income housing tax credits and private financing,” he noted. “In other words, if housing authorities took advantage of the reforms, they could become the entrepreneurial social enterprises that advocates of social housing hope for,” Von Hoffman said.

Quite a few large, high-performing PHAs have exploited new ways to finance, develop, and own low-income residences, Von Hoffman said. As a result, they control tens of thousands of units outside the traditional HUD-assisted public housing stock and are well suited to expand their activities, for example, by providing services to other housing agencies or operating across large geographic areas.

“So far, however, most PHAs, especially those in small towns and rural areas, have not fully exploited the reform programs,” von Hoffman said. “Perhaps in time they will.”

He adds that in order to become agents of a new social housing order, these housing authorities will have to surmount their history and present circumstances.

See von Hoffman’s full paper, which explores the potential role of the public sector in a new social housing system, at the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University website.