With more and more programs addressing the needs of middle-income renters—those earning between 60% to 120% of the area median income (AMI)—Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies decided to dive deep to discover who these renters are, the challenges they face, and the services they need, recently publishing the paper “Subsidizing the Middle: Policies, Tradeoffs, and Costs of Addressing Middle-Income Affordability Challenges.”

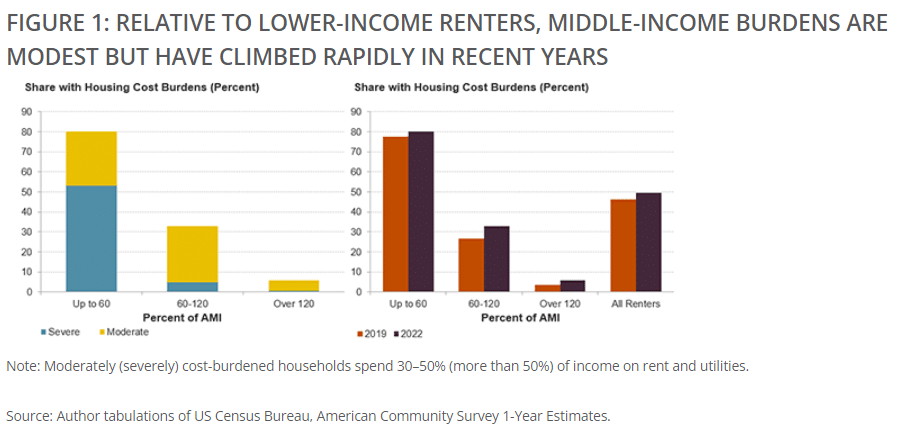

In 2022, more than 14 million renter households could be designated middle-income. While these renters do not face all the hardships of lower-income households, where an incredible 80% of renters had cost burdens in 2022, middle-income renters are not immune from adversity. About 33% middle-income renters were cost burdened in 2022, up 6.3% from only three years ago.

Not surprisingly, cost burdens decline as incomes rise:

- 47% of renters were cost-burdened in the 60%-80% AMI range.

- 28% of renters were cost-burdened in the 80%-100% AMI range.

- 17% of renters were cost-burdened in the 100%-120% AMI range.

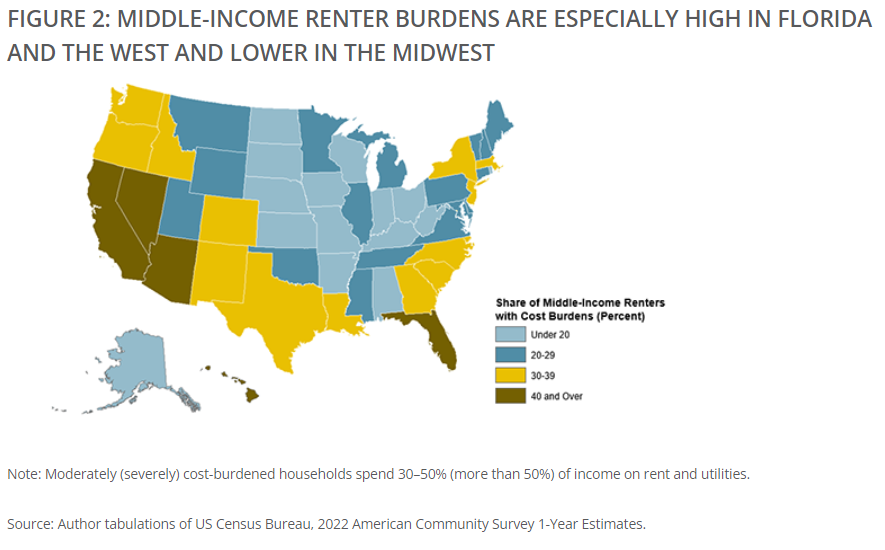

Geographically, middle-income cost burdens were higher in Florida and the West and lower in the Midwest. (Lower-income households have high cost-burdens across the country.) Florida leads with the highest middle-income renter cost burdens at 55%, followed by Hawaii (50%), Nevada (49%), and California (49%). Conversely, only 6% of North Dakota middle-income renters were burdened.

Not surprisingly, middle-income renter households with cost burdens had more leftover income after rent and utilities than lower-income renters. The former had about $2,900 in residual monthly income in 2022; even those in the 60%-80% AMI bracket still had $2,500 remaining after housing expenses, while burdened lower-income renters only had $600 a month left over. High housing costs limit middle-income renters’ ability to build savings for emergencies, retirement, or a downpayment, much less allow them to reach full financial stability. It is much more dire for lower-income renters, who are forced to make more urgent sacrifices, spending less on food and healthcare just to make the rent each month.

By creating a true profile of middle-income renter households, JCHS hopes to reveal their needs and affordability challenges. By definition, middle-income renters have higher earnings and greater earning potential. The national median household income for middle-income renters was at $63,000 in 2022, almost three times the median household income of lower-income renters, at only $21,000.

Education and ethnicity are also factors. In terms of schooling, 41% of cost-burdened middle-income renter households headed by someone with a bachelor’s degree, compared to 19% of lower-income renters, and middle-income renter households were more likely to be headed by someone in their peak earning years. They were also far more likely to be headed by a non-Hispanic white person than a person of color, possibly compounding racial inequities if households with larger AMI percentages were to receive subsidies.

The differences between the two income brackets are noticeable:

- 51% of cost-burdened middle-income renter households are headed by a white person, compared to 41% of cost-burdened lower-income renter households.

- 22% of cost-burdened middle-income renter households are headed by a Hispanic person, compared to 23% of cost-burdened lower-income renter households.

- 17% of cost-burdened middle-income renter households are headed by a Black person, compared to 24% of cost-burdened lower-income renter households.

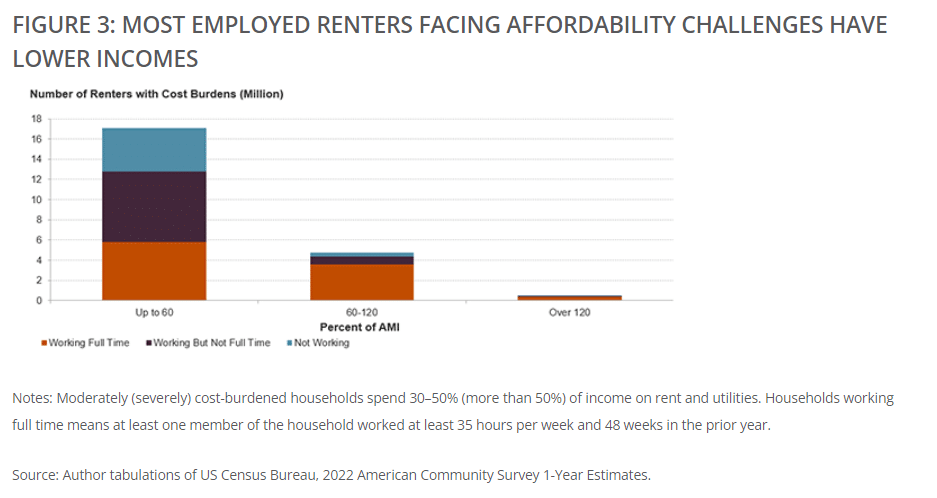

One problem with many state and local housing programs created to address the affordability challenges of middle-income households is that they target households based on the area’s median income. Using this metric, the programs might miss the large majority of cost-burdened households with lower incomes. For instance, 9.8 million renters working full time have cost burdens, but the number of lower-income renter households with burdens far exceeded the number of cost-burdened middle-income renter households by over 60% (5.8 million households vs. 3.6 million). Even working full time did not guarantee affordable housing, especially at lower-income levels: 79% of lower-income renters with at least one adult employed full-time were cost burdened in 2022. Middle-income renter households were not immune to the problem, with 31% having cost burdens.

The study notes that it is important to contextualize the affordability challenges of middle-income renter households, focusing the housing programs and policies on those who most need them. Taken as a whole, these programs could disproportionately target households with fewer economic problems and who face fewer barriers to opportunity due to systemic racism (e.g., in education, employment, and housing). They could also accidentally bypass those that need the programs the most. As such, state and local policies should be carefully written to serve the middle-income renters with the greatest need in markets that do not serve them properly. It is also important to insure that middle-income aid never replaces subsidies for lower-income renters.

Policymakers also need to consider alternatives for assisting middle-income renters than simply direct subsidies. Some cost-effective methods include loosening restrictive zoning ordinances, expediting permit processes, and providing density bonuses for projects that hit a specified affordability level. By reducing the overall cost per unit, these projects could create affordability for middle-income renters without investing public dollars or diverting aid from lower-income households.

Click here to read more on the Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies latest report on middle-income renters.